We are going to invite the public to register the things they care about the most – defined in terms of Values as defined by Schwartz (‘…guiding principles…’ and Rokeach (‘…desirable end states of existence…’. We are going provide a platform for people to express their personal values and to build a fair and representative collective value agenda – together with a register of ways to realise that agenda (‘Prospects’).

This post outlines how Values will be categorised and related in the first Value Prospecting prototype(s) and introduces readymade sources of values to seed the initial database.

Context

Working on the principle that we/societies/communities tend to manage what we measure, and that most collective issues are best addressed through social processes – the Value Prospecting project is going to crowdsource a democratic human value agenda, within a system that also develops a portfolio of value informed prospects.

We are going to frame all collective actions as expressions of shared values

- Rokeach: defines Terminal Values as “Desirable end-states of existence”.

- Schwartz “Values are desirable, trans -situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives.”

In principle – we are going to respect and respond to whatever the public say their values are – but we also need to be able to identify, match and process the ‘guiding principles’ and ‘desirable end states’ they/we share widely (and understand how other individuals find their personal values emotionally compelling).

For reasons like fairness and representational legitimacy and to provide for a broad a level of diverse engagement…we are going to start by harvesting all the ideas that the public wish to express and record when asked: –

- ‘What do you think good is’ in terms of human Values…Describe your guiding principles and the end-points-of-existence you desire.

- ‘Describe examples of things that are good’ as Prospects. What are the things that make your life worthwhile – what do you actually do and like to do with you’re time? What do you find rewarding and meaningful? What do you want most out-of-life and what would you value most in-you-life that you do not have yet?

Of course, some of our most personal Wants, Needs and Aspirations are incompatible with other people’s. VP aims to help people empathise with each other by scaffolding a ‘sense making’ dialogue (‘generating light not heat’) – better to understand our effects on others

Distinguishing Needs, Wants and Values.

Before considering how to use one of the two largest sources of insight and data available for human values around the world (ESS and WVS), we need to clarify how we are going to model, represent and relate Values, Needs and Wants.

When crowdsourcing a description of what people value the most, people in physical poverty may talk about things like food, water, shelter. We are going to classify the Values and Prospects associated with emotional and physical poverty as (existential) Needs.

In VP everyone has a representative profile (especially those who have not represented themselves). All profiles representing people with existential needs will be tagged.

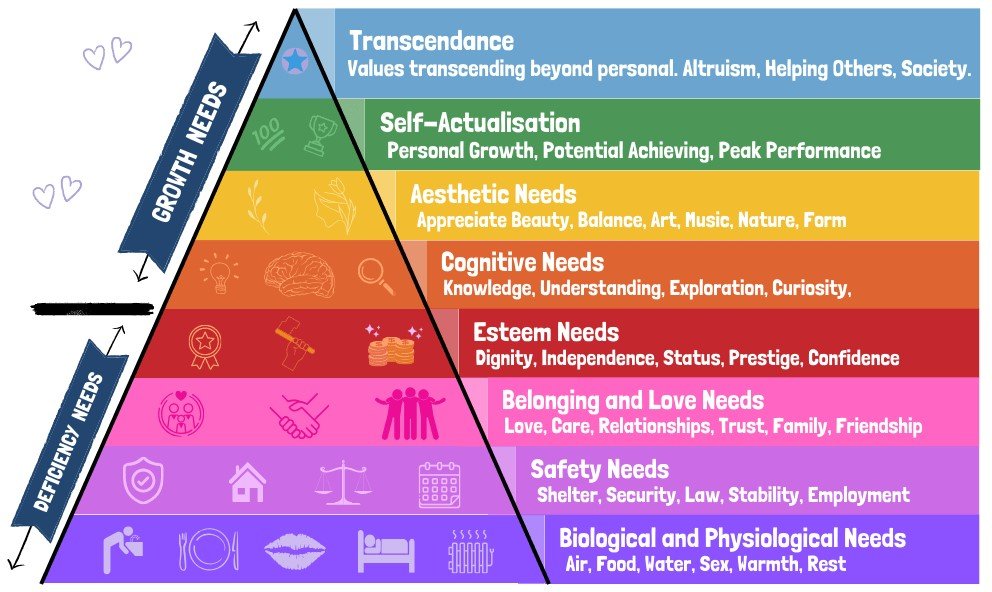

Although Maslow frames all motivations as Needs, in VP we are going to restrict the Need category to the base level of his hierarchy (shown above as Deficiency Needs). The upper segments of Maslow’s hierarchy (Growth Needs), will be represented as Personal Values and Social (or Community) Values.

What are Wants – how are we modelling them?

People’s immediate concerns often reflect their Wants — impulses toward short-term goals or acquisitions that are not as existential as Needs. In VP we are going to define Wants as a particular type of Prospect (normally as Personal Prospects).

Wants might relate to major life events, such as forming friendships, moving out, choosing a job, falling in love, homemaking, or having children. Capturing Wants as Prospects allows us to reflect on their underlying values, explore alternatives, and surface potential unforeseen impacts on others through crowdsourcing and dialogue.

It is important to note that Maslow’s layers do not replace or eclipse each other ‘as the person ascends’. In VP they rather seen as a whole network of ever-present factors with different weighs in different perceived contexts…While poverty naturally emphasises lower-level Needs and might be thought to lead to transactional, selfish (dog eat dog) behaviours, in fact, marginalised and poor communities often demonstrate acts of kindness, generosity, and social cooperation that may be less visible in materially affluent but more transactional environments.

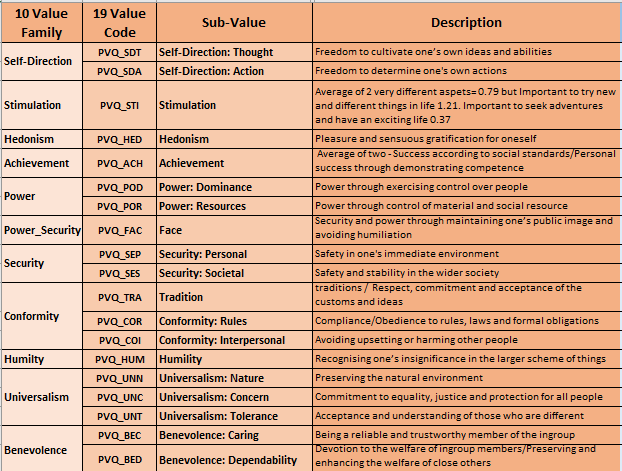

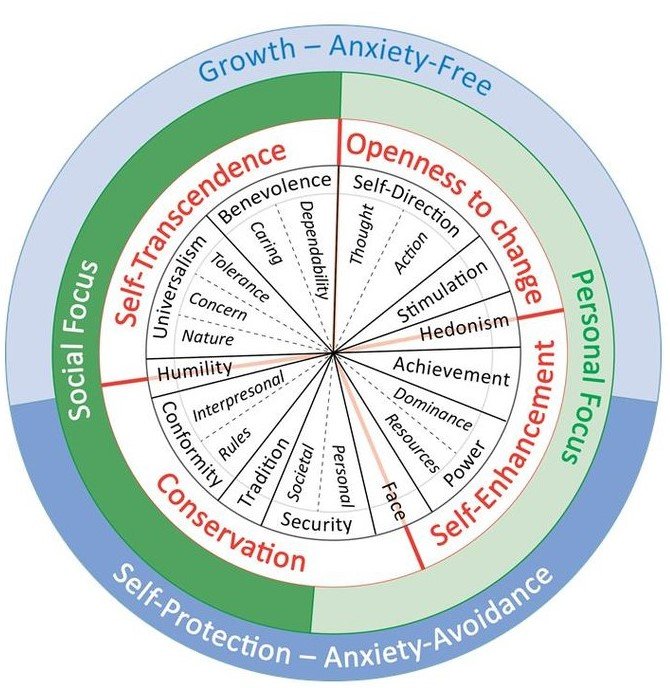

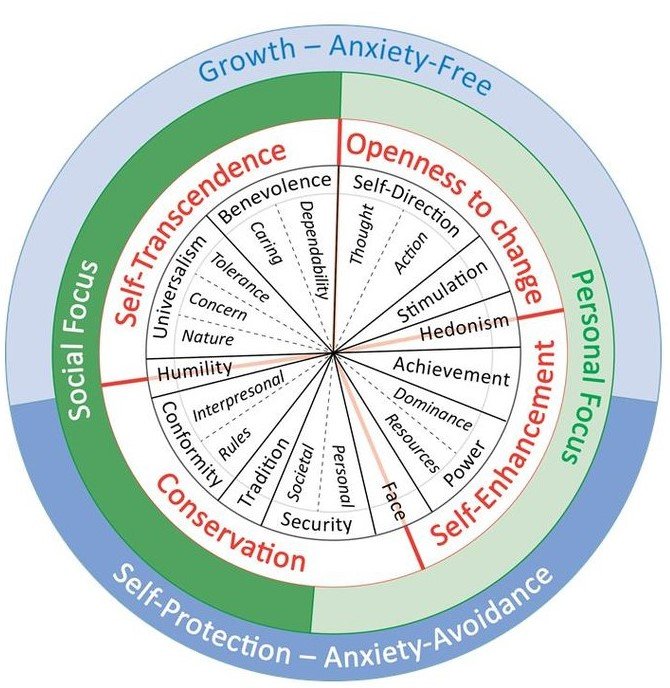

Schwartz divided a circular human value continuum into radial segments. Initially defining 10 core base values which he later increased to 19. Each value had to respond to personal biological survival needs, the requirements for social organisation and the survival of the group itself. He grouped values using dimensions similar to personality traits (Risk aversion, Personal vs Social focus, Transcendence vs Enhancement of the self, Openness to change).

We are going to use ESS data based on Schwartz as a starting point for the prototype.

There is a lot of data collated in the European Social Survey (started in 2002 and completed every 2 years) – including many of the Schwartz 19 values in the latest round (11).

Our test database will hold all the data in one of the ESS rounds (9 or 11) but not all of the fields will initially be relevant. An additional field categorising values as Personal or Social (or indeed separated tables) will be required for Value Prospecting’s process. This is because we will be considering shared values as forming part of a societal agenda – showing the proportionate societal priorities, whilst personal values as part of what makes an individual suited to a particular initiative – useful in presenting to the individual appealing and rewarding actions and options (by default – also aligned with societal values).

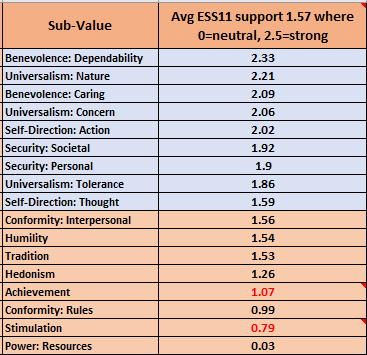

Schwartz values are ranked by importance: The table opposite illustrates the relative importance using averages from ESS11 data (blue section shows above-average values). There is a clear preference for Benevolence, Universalism, and Security. Yet these highly valued aspects of life are not proportionately reflected in most societal agendas.

Security concerns are prominent in political discourse, and although Benevolence and Universalism are prominent in religious agendas they are far less so in the Political, Business and Media (PBM) agendas.

Contrary to public opinion, PBM agendas often highlight short term, personal, self enhancement values like Hedonism, Stimulation, and Power – values with the least natural personal support.

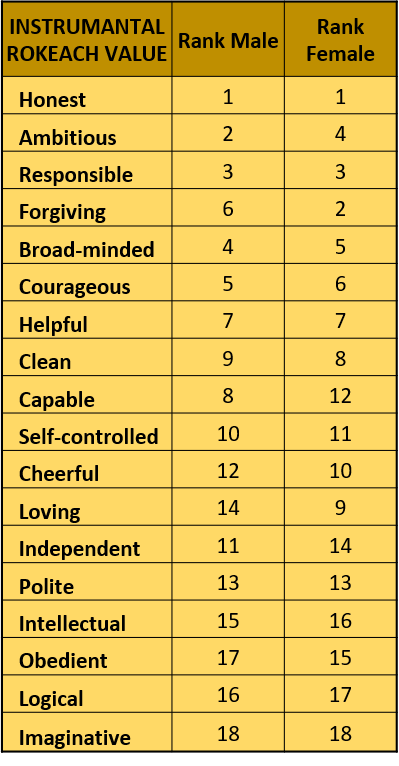

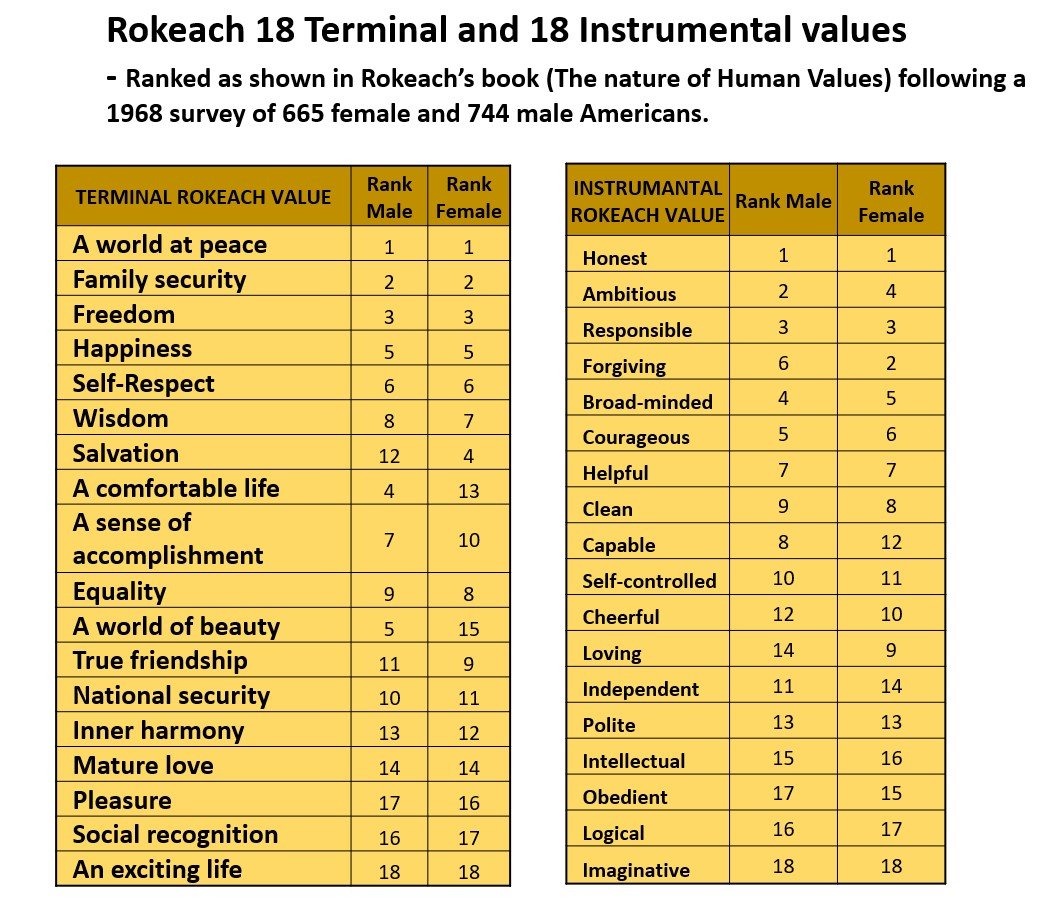

Rokeach listed 18 Terminal and 18 Instrumental values – and ranked them (ref his book ‘The nature of Human Values’) – reporting a 1968 survey of 665 female and 744 male Americans.

In Rokeach’s data we can see again a mix of Social and Personal human values, and a distinct ranking which illustrates the contrast between private (emphasising pro-social) and public (Political, Business and Media agendas).

Again, unlikely though it seems, we don’t appear to have a transparent public process where we can all participate in making sense of these values and aligning our actions with them in a proportionate and fair manner.

This project is about testing tools and techniques to make the crowdsourcing of initiatives (‘Prospects’) practical for everyone. It aims in part to address the failures of large social media systems and business and political systems that depend on generating excitement (‘selling ideas’) to support collective sense making and pro-social learning from which grass roots initiatives emerge (creating a public demand to be satisfied by political and business initiatives).

Sense making across large groups of people depends on emotional and empathetic contact sufficient to build relationships that bridge competing and incompatible world views.

I don’t feel that we need to conclude the discussions about data structures and the nature of values suitable for a usable definition of values. In a rapid application development environment that iterates – we need also to keep the way we realise the programms objectives open to dredesign, here – like a baby learning to walk and control it’s limbs – gross motoer control is more easily learned and fine motor control more easily accomplished by learning first – gross motor control.

I’d like to outline what an ideal situation might be like – from the point of view of ‘calculability’. And then outline a style of framework that is more pragmatic – whilst retaining some of the ideal / calculability features.

Many of us strike a balance between selfishness and selflessness, partly this is because we discount gains that are remote (empathetically, conceptually or in time and location) …

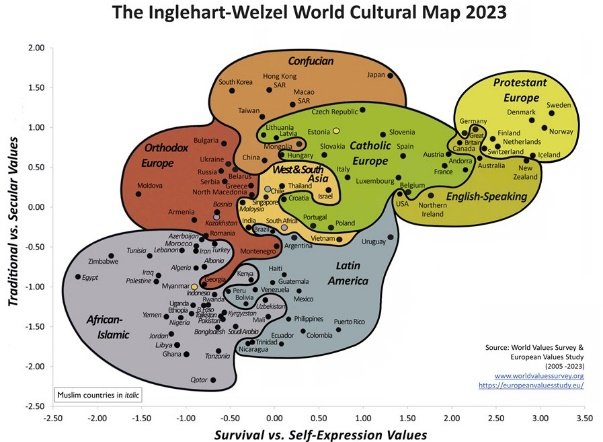

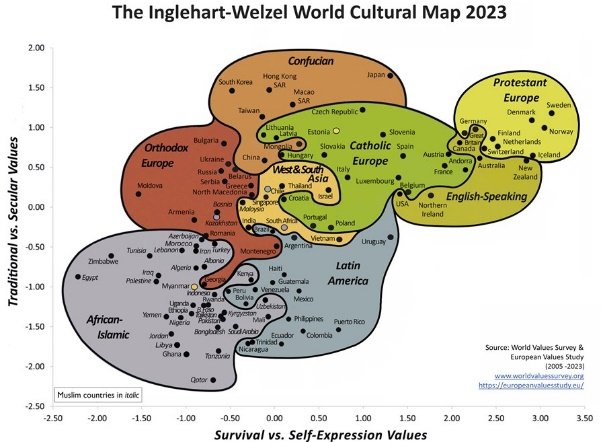

Inglehart-Welzel use World Value Survey data),

…to display cultural differences in value priorities related to geography, religion and material wealth…

Societal values might be considered classes of drivers underlying the publics values assign different priorities (such as those of Maslows 9 part hierarchy) but in Value Prospecting – we are making a natural distinction between our actions and potential actions (Prospects) and the principles that underly our actions and that we can use to judge them (our Values). We are interpreting actions as an expression of values. For example, many people would say that they value ‘Nature’ they want to ‘Protect’ the natural world… Rokeach (see later) would say that valuing Nature for its own sake is a Terminal Value and that ‘Protecting’ living things is an Instrumental one. A project to set up a Nature reserve, or a decision to use an ‘eco’ version of a product (paint, soap, clothing) would be examples of ‘Prospects’ – practical concrete ways to realise those Values. Our Needs, wants and aspirations

prospect These are examples of Values (Terminal and Instrumental respectively) ay want to describe ‘Respect for Nature’ se ideas value their values and actions that produce value. What they need, want and aspire to. and any ideas from the public which help define what they value, we are proabably going to categorise the input define or categorise values tuned to be useful in a social process involving dialogue about values between people, and involving impact assessment of prospects in order to determine how they impact on values. Although many people do not have a coherent world view as such – the values we present to the public will inherently be associated with a particular ‘communications styles’, models, pictures or views – of the world’.

Let’s take a whistlestop tour around the thought domain related to human values. I started by asking ChatGPT (mini-5) to ‘summarise the current most influential sociological and philosophical academic movements characterising human values?’. The full answer is in the appendix.

I asked ChatGPT “Can you summarise the most currently influential sociological and philosophical academic movements characterising human values? State who uses the particular versions and what for.”.

Many of the worlds ‘wicked’ problems have a behavioural, social or cultural element – most of the most important ideas (Justice, Equality, Democracy) are ‘cultural constructs’. Can ICT be used to nurture and maintain pro-social processes like sense making and social learning?

If everything we do is a reflection of our values, and everything we do together is a reflection of shared values…Can we register our values online and crowdsource ways to generate more value through the things we do?

I’d like to outline what an ideal situation might be like – from the point of view of ‘calculability’. And then outline a style of framework that is more pragmatic – whilst retaining some of the ideal / calculability features.

Many of us strike a balance between selfishness and selflessness, partly this is because we discount gains that are remote (empathetically, conceptually or in time and location) …

Definitions of human Value.

The most popular scales for measuring values in recent years are those of Hofstede (1980, 1991), Rokeach (1967, 1973), Inglehart (1971), and Schwartz (1992). I discuss each in turn.

Hofstede.

Hofstede proposed four value dimensions for comparing cultures. He characterized the value profiles of 53 nations or cultural regions, using data from IBM employees. A great deal of research has built on Hofstede’s findings (see, Kagitcibasi, 1997, for example).

His scale is unsuited for the ESS, however. This scale is not intended for use in linking individuals’ value orientations to their opinions or behavior. The dimensions it measures (e.g., individualism, power distance) discriminate among national cultures but do not discriminate among individual persons. Moreover, most of the Hofstede items refer to work values. They do not measure the range of human values relevant in many life domains.

Rokeach.

The Rokeach scale asks respondents to rank each of two sets of 18 abstract values from the most to the least important. Many studies with this scale have identified meaningful relations of values to a variety of demographic variables, opinions, attitudes, and behavior (bibliography in Braithwaite & Scott, 1991).

This scale is not well-suited for the ESS either, however. Despite its intention of covering the range of human values comprehensively, it leaves out critical content (e.g., tradition and power values). The selection of items was not theory-driven, so predictions and explanations based on it are typically ad hoc. Finally, on technical grounds, it is both too long (36 items) for the ESS and too abstract for use with the less educated subgroups in representative samples.

Inglehart.

The widely used Inglehart measures of materialism/postmaterialism (MPM) are short enough in both their four and twelve item versions to be considered for the ESS. They are based in theory, they are apparently well-understood by the respondents in representative samples, and they have shown meaningful relations to many variables of interest to survey researchers (Inglehart, 1997). Moreover, persuasive arguments have been made to support the view that they tap an important value shift in the West.

On the other hand, these scales suffer from a number of limitations that make them less than optimal scales for the ESS. First, as noted above, some of the Inglehart items are highly sensitive to prevailing economic conditions. And others may be sensitive to whether or not the respondent supports the current governing party (see below). Such sensitivity is desirable for items intended to measure changing opinions, but it may yield a misreading of deeply rooted value orientations and their vicissitudes. Second, this scale measures individuals’ values only indirectly. It asks about preferences among possible goals for one’s country, not about personal goals. These preferences presumably reveal individual’s own valuing of economic and physical security, of freedom, self-expression, and the quality of life. But multiple individual values are likely to underlie responses to questions about political, economic and security aspirations for one’s country. Choosing “protecting freedom of speech” as the most important future goal for society, for example, presumably reflects individual values of intellectual openness and tolerance of others. But in particular personal or sociopolitical circumstances, it might be the choice of an intolerant member of a conservative fringe group who fears government control.

Third, the Inglehart scale measures only a single value dimension. Broad and important as the MPM dimension may be, it is not fine-tuned enough to capture the rich variation in individual value orientations. Research in seven countries (see below) suggests that MPM combines many distinguishable value emphases into a single score. As discussed below, each of these ten value emphases have distinct correlates. These cannot be studied with scores on the single dichotomous MPM variable. Although MPM would not provide adequate coverage of basic value orientations for the ESS, it would make sense to include the 4-item scale in the first one or two surveys, if possible. This would permit comparisons of the associations with other values included in the ESS. Such comparisons would make it possible to link 266 findings from past surveys with MPM to the more fine-tuned value orientations studied in the ESS.

Schwartz.

The Schwartz (1992) Value Survey (SVS) is currently the most widely used by social and cross-cultural psychologists for studying individual differences in values. The conception of values that guided its development derived directly from the six features of values outlined above. This scale asks respondents to rate the importance of 56 specific values as “guiding principles in your life” [e.g., SOCIAL JUSTICE (correcting injustice, care for the weak)]. These specific values measure ten, theory-based value orientations. Studies in over 65 countries support the distinctiveness of these value orientations (Schwartz, 2003). However, the length of this scale precludes its use in the ESS. Moreover, people with little or no education encounter difficulty when responding to it. The method I propose for the ESS is based on the same theory as the Schwartz scale and research with this scale is relevant to the proposed method as well

1. Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values (Social Psychology / Sociology)

Concept:

- Values are universal, motivational constructs that guide behaviour across contexts.

- Organized in a circular structure with higher-order dimensions: Openness to Change, Conservation, Self-Transcendence, Self-Enhancement.

Users / Applications:

- Widely used in cross-cultural research, surveys (European Social Survey, World Values Survey).

- Policy analysis, organizational behaviour, social marketing, ethics research.

Purpose:

- To compare value priorities across individuals, groups, and cultures.

- To predict behaviour, societal change, or cultural shifts.

Example: Academics in social psychology, sociology, and management studies (Schwartz, 2012; Roccas & Sagiv, 2010).

2. Rokeach Value Survey (RVS) / Instrumental & Terminal Values (Social Psychology / Sociology)

Concept:

- Distinguishes between end-states (terminal values) and modes of behaviour (instrumental values).

- Values are learned beliefs about what is preferable in life.

Users / Applications:

- Organizational studies, leadership research, ethical decision-making studies.

- Often used in applied psychology, management, or marketing research.

Purpose:

- To understand motivation, predict ethical behaviour, guide leadership or HR policies.

Example: Milton Rokeach, used in applied social psychology and business studies.

3. Postmaterialist and Cultural Value Theory (Ronald Inglehart, Sociology / Political Science)

Concept:

- Societies shift from materialist values (economic, physical security) to postmaterialist values (self-expression, environmental protection).

- Values shape political orientation, civic engagement, and social norms.

Users / Applications:

- Political science, sociology, policy research, cross-national comparisons.

- Used to forecast social change, voting patterns, and cultural evolution.

Purpose:

- To understand generational and cultural shifts in priorities.

- To guide policy, survey design, or societal development programs.

Example: European Social Survey, World Values Survey, political sociology studies.

4. Axiology / Philosophical Ethics (Philosophy)

Concept:

- Values are standards of worth or goodness, often normative (how people ought to act).

- Explored as moral, aesthetic, and practical values.

- Philosophical debates often distinguish intrinsic vs instrumental value, objective vs subjective value.

Users / Applications:

- Ethical theory, applied philosophy, bioethics, AI ethics.

- Used by ethicists, philosophers of law, and social theorists.

Purpose:

- To ground moral reasoning and human flourishing.

- To analyse obligations, rights, and societal priorities.

Example: Contemporary ethics: Peter Singer (utilitarian ethics), Christine Korsgaard (Kantian ethics applied to practical reason).

5. Virtue Ethics / Human Flourishing (Aristotelian / Neo-Aristotelian Philosophy)

Concept:

- Values are expressed as virtues necessary for eudaimonia (human flourishing).

- Focus on character traits (honesty, courage, justice) rather than abstract rules.

Users / Applications:

- Moral education, leadership development, applied ethics.

- Used to guide personal and organisational development.

Purpose:

- To cultivate practical wisdom and ethical action.

- To define what constitutes a “good life” for individuals and communities.

Example: Alasdair MacIntyre (modern virtue ethics), Martha Nussbaum (capabilities approach).

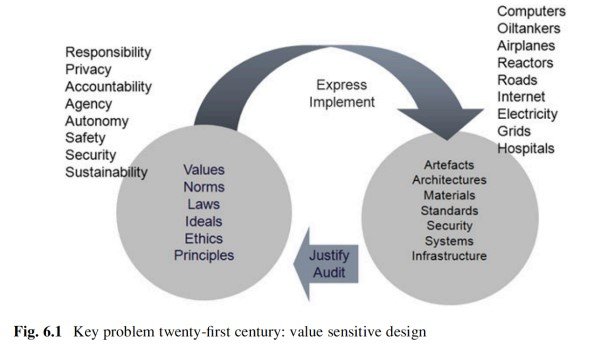

6. Value Sensitive Design (VSD) / Technology Ethics

Concept:

- Values are embedded in technology and design choices.

- Emphasizes participatory processes to ensure that technology reflects stakeholder values.

Users / Applications:

- Human-computer interaction, AI ethics, software engineering, participatory design.

- Applied by computer scientists, designers, and social engineers.

Purpose:

- To operationalize values into real-world systems.

- To mediate between individual, societal, and organizational value conflicts.

Example: Batya Friedman, Peter H. Kahn Jr., in academic HCI and technology ethics research.

7. Social Constructionist / Relational Values (Sociology / Environmental Studies)

Concept:

- Values are constructed through social interaction, not fixed.

- Focus on relational, collective, or ecological values (e.g., stewardship, community well-being).

Users / Applications:

- Environmental governance, sustainability studies, participatory development.

- Used by sociologists, environmental scientists, and policy makers.

Purpose:

- To design policies and interventions that resonate with community-held priorities.

- To understand how cultural context shapes perceived importance of different values.

Example: Arild Vatn (environmental economics), Robert Costanza (ecosystem services and relational values).

Summary Table

| Movement / Theory | Key Concept of Values | Users / Fields | Purpose / Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schwartz | Universal, motivational values, circular structure | Social psychology, sociology, policy research | Cross-cultural comparison, behaviour prediction |

| Rokeach | Terminal & instrumental values | Applied psychology, leadership studies | Motivation, ethical behaviour, HR policies |

| Inglehart / Postmaterialism | Materialist vs postmaterialist generational values | Sociology, political science | Predict societal change, voting, civic engagement |

| Philosophical Axiology | Standards of worth / goodness | Philosophy, ethics | Ground moral reasoning, normative analysis |

| Virtue Ethics | Values as virtues for human flourishing | Moral education, applied ethics | Guide practical action, human development |

| Value Sensitive Design (VSD) | Values embedded in technology | HCI, AI ethics, software design | Operationalize values in systems, mediate conflicts |

| Social Constructionist / Relational | Values as socially constructed, relational | Sociology, sustainability, environmental policy | Align interventions with community and ecological priorities |

Values

The European Social Survey uses 10 values in the spectrum – and there are two questionnaires for this ( Measuring the Refined Theory of Individual Values in 49 Cultural Groups: Psychometrics of the Revised Portrait Value Questionnaire – PMC)

The 40 item PVQ-40 (Schwartz, 2003) successfully measures the 10 basic values (e.g., Cieciuch & Schwartz, 2012). The PVQ-21, used in European Social Survey, succeeds in differentiating only 7 of the 10 values, requiring that some pairs of values be combine (Davidov et al., 2008).

When Schwartz proposed his refined value theory that distinguishes 19 values in the value circle, he designed a 57-item PVQ. This PVQ has undergone several revisions (the PVQ-5X, Schwartz et al., 2012; the PVQ-R, Schwartz et al., 2017; Tamir et al., 2016; the PVQ-RR, Schwartz, 2017). This study presents the psychometric properties of the PVQ-RR in a large set of cultural groups for the first time. Several sources describe how the finer distinctions of the 19 values provide new insights into the relations of values to attitudes, behaviours, personality, and demographics (Hanel et al., 2018; Schwartz, 2017; Schwartz et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2017)

So we could use PVQ21 like ESS (to get 7 out of 10, PVQ40 to get 10/10 or PVQ-RR to try for 19…

Here is an example https://aidaform.com/templates/pvq-test.html

Leave a Reply